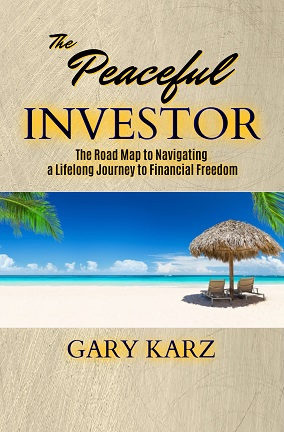

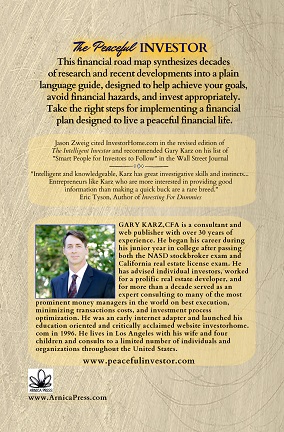

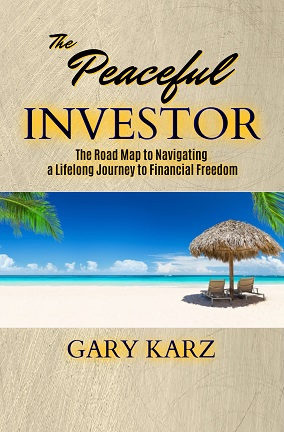

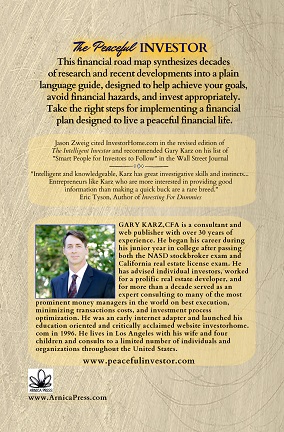

Buy The Peaceful Investor at Amazon

Table of Contents and Launch Site

I am offering the online chapters of the book using "The Honor System." Tip options at the bottom of the page.

The rapid evolution of computer technology in recent decades has provided investment professionals (and amateurs) with the capability to access and analyze tremendous amounts of financial data. As a result, some of the more intriguing debates have revolved around the practice and consequences of "data mining."

Data mining involves searching through databases for correlations and patterns that differ from results that would be anticipated to occur by chance, or in random conditions. The practice of data mining in and of itself is neither good nor bad, and the use of data mining has become common in many industries. For instance, in an attempt to improve life expectancy researchers might use data mining to analyze causes and correlations with death rates. Data mining is also used by advertisers and marketing firms to target consumers. But possibly the most notorious group of data miners are stock market researchers that seek to predict future stock price movement. Most, if not all stock market anomalies have been discovered (or at least documented) via data mining of past prices and related (or sometimes unrelated) variables.

When market beating strategies are discovered via data mining, there are a number of potential problems in making the leap from a back-tested strategy to successfully investing in future real world conditions. The first problem is determining the probability that the relationships occurred at random or whether the anomaly may be unique to the specific sample that was tested. Statisticians are fond of pointing out that if you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything. There are also other terms such as data snooping, data dredging, and data fishing which may be defined differently by some, but tend to have some overlap.

In one often referenced example, David Leinweber went searching for random correlations to the S&P 500. Peter Coy described Leinweber's findings in a June 16, 1997 Business Week article titled "He who mines data may strike fool's gold." The article discussed the fact that patterns will occur in data by pure chance, particularly if you consider many factors. Many cases of data mining are immune to statistical verification or rebuttal. In describing the pitfalls of data mining, Leinweber "sifted through a United Nations CD-ROM and discovered that historically, the single best predictor of the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index was butter production in Bangladesh." The lesson to learn according to Coy is a "formula that happens to fit the data of the past won't necessarily have any predictive value."

“Back testing has always been a suspect class of information . . . When you look backwards, you're only going to show what's good.”Barry Miller1

![]() Anomalies discovered through data mining are considered to be more significant as the period of time increases and if the anomaly can be confirmed in out of sample tests over different time periods and comparable markets (for instance on foreign exchanges). If an anomaly is discovered in back tests, it’s also important to determine how costs (transactions costs, the bid-ask spread, and impact costs for institutional traders) would reduce the returns. Some anomalies are simply not realizable. Additionally, strategies that have worked in the past may simply stop working as more investors begin investing according to the strategy.

Anomalies discovered through data mining are considered to be more significant as the period of time increases and if the anomaly can be confirmed in out of sample tests over different time periods and comparable markets (for instance on foreign exchanges). If an anomaly is discovered in back tests, it’s also important to determine how costs (transactions costs, the bid-ask spread, and impact costs for institutional traders) would reduce the returns. Some anomalies are simply not realizable. Additionally, strategies that have worked in the past may simply stop working as more investors begin investing according to the strategy.

![]() The "Dogs of the Dow" is a stock picking strategy that had become popular at various times in recent decades. Proponents of the strategy argue that it performed well relative to the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) and other indexes. As a result, thousands of investors have invested in various "Dogs of the Dow" strategies, either individually, or through packaged funds. Unfortunately, while the track record was at times undeniably impressive, there are a number of reasons for those considering the strategy to waiver.

The "Dogs of the Dow" is a stock picking strategy that had become popular at various times in recent decades. Proponents of the strategy argue that it performed well relative to the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) and other indexes. As a result, thousands of investors have invested in various "Dogs of the Dow" strategies, either individually, or through packaged funds. Unfortunately, while the track record was at times undeniably impressive, there are a number of reasons for those considering the strategy to waiver.

![]() Strategies of investing in unpopular stocks in the DJIA are nothing new. In fact, an astute reader of Benjamin Graham's classic The Intellient Investor can find a reference to a study by H. G. Schneider published in the June 1951 issue of the Journal of Finance that documented a strategy of investing in unpopular DJIA issues from 1917-1950. A second study noted in the book covers the years 1933-1969. The studies looked at strategies of buying either the six or ten issues in the DJIA selling at the lowest earnings multiples and rebalancing at holding periods ranging from one to five years. The strategy proved unprofitable from 1917-1933 but from 1937-1969 a strategy of investing in the low multiple ten soundly and consistently beat the high multiple ten and the DJIA.

Strategies of investing in unpopular stocks in the DJIA are nothing new. In fact, an astute reader of Benjamin Graham's classic The Intellient Investor can find a reference to a study by H. G. Schneider published in the June 1951 issue of the Journal of Finance that documented a strategy of investing in unpopular DJIA issues from 1917-1950. A second study noted in the book covers the years 1933-1969. The studies looked at strategies of buying either the six or ten issues in the DJIA selling at the lowest earnings multiples and rebalancing at holding periods ranging from one to five years. The strategy proved unprofitable from 1917-1933 but from 1937-1969 a strategy of investing in the low multiple ten soundly and consistently beat the high multiple ten and the DJIA.

![]() More recently excitement was focused on high dividend yield stocks in the DJIA. Outperformance of high dividend Dow stocks was apparently discovered by John Slatter in the late 1980's. The strategy began to increase in popularity in the early nineties following publication of Michael O'Higgins book Beating The Dow. The Dow-10 strategy consists of buying the ten highest yielding DJIA stocks and rebalancing annually. Some proponents "tweak" the Dow-10 strategy by ranking those ten according to price and selecting the lowest priced of the five.

More recently excitement was focused on high dividend yield stocks in the DJIA. Outperformance of high dividend Dow stocks was apparently discovered by John Slatter in the late 1980's. The strategy began to increase in popularity in the early nineties following publication of Michael O'Higgins book Beating The Dow. The Dow-10 strategy consists of buying the ten highest yielding DJIA stocks and rebalancing annually. Some proponents "tweak" the Dow-10 strategy by ranking those ten according to price and selecting the lowest priced of the five.

![]() The Motley Fool endorsed their modification in The Motley Fool Investment Guide. "The Foolish Four" consisted of investing 40% of a portfolio in the second lowest priced of the ten and 20% each in the third, fourth, and fifth lowest priced. The rational for "The Foolish Four" strategy was back-tested results showing the strategy to have yielded 25.5% annually over a twenty year period.

The Motley Fool endorsed their modification in The Motley Fool Investment Guide. "The Foolish Four" consisted of investing 40% of a portfolio in the second lowest priced of the ten and 20% each in the third, fourth, and fifth lowest priced. The rational for "The Foolish Four" strategy was back-tested results showing the strategy to have yielded 25.5% annually over a twenty year period.

![]() The 11th chapter of The Motley Fool Investment Guide addressed some counter arguments to investing in the strategy. The first issue is volatility and diversification. Both the Foolish Four and the Dow-10 are likely to be more volatile and riskier than investing in the DJIA or a broader index. The second issue is the relevance of the twenty year period. On that page, the authors disclosed that a staff member had indeed run the numbers back to 1961. So the 25% returns were only achievable if you happened to start investing in the strategy precisely at the right time. The longer term results brought the annual rate down to 18.35% - still a healthy lead over the market's 10.02%, but not nearly as impressive (there were apparently no investors claiming to have actually used the strategy for either period).

The 11th chapter of The Motley Fool Investment Guide addressed some counter arguments to investing in the strategy. The first issue is volatility and diversification. Both the Foolish Four and the Dow-10 are likely to be more volatile and riskier than investing in the DJIA or a broader index. The second issue is the relevance of the twenty year period. On that page, the authors disclosed that a staff member had indeed run the numbers back to 1961. So the 25% returns were only achievable if you happened to start investing in the strategy precisely at the right time. The longer term results brought the annual rate down to 18.35% - still a healthy lead over the market's 10.02%, but not nearly as impressive (there were apparently no investors claiming to have actually used the strategy for either period).

![]() The third issue discussed in The Motley Fool Investment Guide was overpopularity. They argued that "sales of our book are not going to wreak havoc" with the market. Ironically, they probably underestimated their own future success, having gone on to become extremely popular for some time. But the issue was much larger. The Motley Fool was, after all, only elaborating on O'Higgin's book and they were only one of many organizations hyping related strategies. Barron's (which coined the phrase "Dogs of the Dow") and many others had also documented the strategy and numerous mutual funds and trusts had sprouted up attempting to cash in. The Select-10, a unit trust (actually made up of a number of funds) that invested in the Dow-10 had grown to over $14 billion and several commentators estimated that over $20 billion was investing in Dow dividend strategies. According to Andrew Bary's December 28, 1998 column in Barron's (titled "Bound for the Pound?"), the Select 10 trust had become the largest holders of “Dow Dogs” J.P. Morgan, International Paper, and Kodak.

The third issue discussed in The Motley Fool Investment Guide was overpopularity. They argued that "sales of our book are not going to wreak havoc" with the market. Ironically, they probably underestimated their own future success, having gone on to become extremely popular for some time. But the issue was much larger. The Motley Fool was, after all, only elaborating on O'Higgin's book and they were only one of many organizations hyping related strategies. Barron's (which coined the phrase "Dogs of the Dow") and many others had also documented the strategy and numerous mutual funds and trusts had sprouted up attempting to cash in. The Select-10, a unit trust (actually made up of a number of funds) that invested in the Dow-10 had grown to over $14 billion and several commentators estimated that over $20 billion was investing in Dow dividend strategies. According to Andrew Bary's December 28, 1998 column in Barron's (titled "Bound for the Pound?"), the Select 10 trust had become the largest holders of “Dow Dogs” J.P. Morgan, International Paper, and Kodak.

![]() Incidentally, at the start of 1998, the Motley Fool "modified" The Foolish Four formula. The second variation invested equally in the four lowest priced of the Dow-10 over 18 month periods, however if the lowest priced of the ten is also the highest yielding stock, it was thrown out and the second through fifth lowest priced are used. The new version was described in You Have More Than You Think. The Foolish Four was modified a third time some time later.2

Incidentally, at the start of 1998, the Motley Fool "modified" The Foolish Four formula. The second variation invested equally in the four lowest priced of the Dow-10 over 18 month periods, however if the lowest priced of the ten is also the highest yielding stock, it was thrown out and the second through fifth lowest priced are used. The new version was described in You Have More Than You Think. The Foolish Four was modified a third time some time later.2

![]() As for O'Higgin's, he was no longer investing in the Dow Dogs at all according to a December 8, 1997 Time magazine article. The article “The Dow Dogs Won't Hunt” quoted O'Higgins as noting that the Dow Dogs "have become too popular and the market has become too high" for the gambit to keep working.

As for O'Higgin's, he was no longer investing in the Dow Dogs at all according to a December 8, 1997 Time magazine article. The article “The Dow Dogs Won't Hunt” quoted O'Higgins as noting that the Dow Dogs "have become too popular and the market has become too high" for the gambit to keep working.

![]() An interesting discussion of the Dow Dogs theory was also included in Peter Tanous' 1997 book Investment Gurus. In it, Tanous and William Sharpe discussed the strategy in the context of value investing. Sharpe made the point that on one hand, if you search hard enough with a large number of random data sets, you will eventually "find some strategy that would have made you a fortune." On the other hand, the results from the strategy could be the value stock effect. An argument can be made in favor of the Dow Dividend strategy given the scores of studies that have documented outperformance of "value" stocks.

An interesting discussion of the Dow Dogs theory was also included in Peter Tanous' 1997 book Investment Gurus. In it, Tanous and William Sharpe discussed the strategy in the context of value investing. Sharpe made the point that on one hand, if you search hard enough with a large number of random data sets, you will eventually "find some strategy that would have made you a fortune." On the other hand, the results from the strategy could be the value stock effect. An argument can be made in favor of the Dow Dividend strategy given the scores of studies that have documented outperformance of "value" stocks.

![]() Louis Rukeyser, was the popular host of Wall $treet Week and he discussed the Dogs of the Dow on his February 5, 1999 show. His comments included the following:

Louis Rukeyser, was the popular host of Wall $treet Week and he discussed the Dogs of the Dow on his February 5, 1999 show. His comments included the following:

Let's recall the wisdom of late financial genius G. M. Loeb who once told me ‘Lou, whenever you think you've found the key to the market, some SOB changes the lock.’ Lately a lot of new comers to finance have been trumpeting an alleged sure-fire way to beat the averages by buying the so-called Dogs of the Dow. The problem is, as a little research reveals, that in more years than not of late, they really were dogs . . . By the way, it used to be that the real Dogs of the Dow were simply the indexes ten worst performers of the prior year, but that theory didn't work as promised. So supporters apparently figured that this way would give them a better shot . . . Vast amounts of phony commentary have been paraded on this subject and mutual funds and Unit Investment Trusts have been formed to exploit the market. But the reality is, as with so many so-called sure-fire theories, that just about the time you hear about it, somehow it stops working.

![]() A rigorous analysis of the Dow strategies topic was published in the July/August 1997 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal. In "Does the 'Dow-10 Investment Strategy' Beat the Dow Statistically and Economically?" Grant McQueen, Kay Shields, and Steven Thorley thoroughly analyzed the strategy from 1946 to 1995 and addressed the issues of risk, taxes, transactions costs, and the potential problems of "investor learning" and "data mining." The authors found that the Dow-10 did in fact produce significant excess returns over the 50 year period. The average annual return (arithmetic mean) for the Dow-10 was 16.77% versus 13.71% for the Dow-30. But higher risk as measured by standard deviation (19.10% versus 16.64%) accompanied the higher returns.3

A rigorous analysis of the Dow strategies topic was published in the July/August 1997 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal. In "Does the 'Dow-10 Investment Strategy' Beat the Dow Statistically and Economically?" Grant McQueen, Kay Shields, and Steven Thorley thoroughly analyzed the strategy from 1946 to 1995 and addressed the issues of risk, taxes, transactions costs, and the potential problems of "investor learning" and "data mining." The authors found that the Dow-10 did in fact produce significant excess returns over the 50 year period. The average annual return (arithmetic mean) for the Dow-10 was 16.77% versus 13.71% for the Dow-30. But higher risk as measured by standard deviation (19.10% versus 16.64%) accompanied the higher returns.3

![]() The authors pointed out that more of the Dow-10 returns come from dividends (as you would expect) which can’t be deferred and are taxed at a higher rate. Further the Dow-10 strategy requires annual rebalancing exposing taxable accounts to taxes on gains. The Dow-10 authors stated that a formal analysis of the tax differences is not possible because the tax payments will depend on each individual's tax rate and other considerations. However, transactions costs and risk explain most of the Dow-10 excess return, and they believe that most if not all of the remaining excess return would have gone to the IRS. The authors also looked at sub-periods and found that during some extended periods the strategy outperformed, but during other long stretches (decades) the authors suggest that economically, an investor would have been better off (after adjusting for risk, transactions costs, and taxes) in the DJIA.

The authors pointed out that more of the Dow-10 returns come from dividends (as you would expect) which can’t be deferred and are taxed at a higher rate. Further the Dow-10 strategy requires annual rebalancing exposing taxable accounts to taxes on gains. The Dow-10 authors stated that a formal analysis of the tax differences is not possible because the tax payments will depend on each individual's tax rate and other considerations. However, transactions costs and risk explain most of the Dow-10 excess return, and they believe that most if not all of the remaining excess return would have gone to the IRS. The authors also looked at sub-periods and found that during some extended periods the strategy outperformed, but during other long stretches (decades) the authors suggest that economically, an investor would have been better off (after adjusting for risk, transactions costs, and taxes) in the DJIA.

![]() The authors then discussed the impact of "investor learning" or the tendency for investors following the strategy to drive up the price of the stocks thereby reducing or eliminating excess returns. The authors also discussed "data mining" or the "file drawer problem." They described it as the possibility that certain correlations between variables will occur randomly in financial and other data purely by chance. If one searches long enough these chance or random correlations will be found. However, "the true significance of successful investment strategies can be assessed only after quantifying the number of unreported or unpublished failures gathering dust in the file drawers of stock market analysts, traders, and researchers."

The authors then discussed the impact of "investor learning" or the tendency for investors following the strategy to drive up the price of the stocks thereby reducing or eliminating excess returns. The authors also discussed "data mining" or the "file drawer problem." They described it as the possibility that certain correlations between variables will occur randomly in financial and other data purely by chance. If one searches long enough these chance or random correlations will be found. However, "the true significance of successful investment strategies can be assessed only after quantifying the number of unreported or unpublished failures gathering dust in the file drawers of stock market analysts, traders, and researchers."

![]() I contacted the authors to ask them whether they were aware of the Motley Fools' variation. They had not heard about it at that point, so I told them they really should take a look because I explained it was a clear example of data mining. Having already gathered the data to analyze the Dow Dogs, the Professors followed up by making a case study out of the Motley Fool’s Foolish Four. McQueen and Thorley analyzed the Foolish Four as described in The Motley Fool Investment Guide. That research resulted in another article published in the March/April 1999 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal titled "Mining Fool's Gold."4

I contacted the authors to ask them whether they were aware of the Motley Fools' variation. They had not heard about it at that point, so I told them they really should take a look because I explained it was a clear example of data mining. Having already gathered the data to analyze the Dow Dogs, the Professors followed up by making a case study out of the Motley Fool’s Foolish Four. McQueen and Thorley analyzed the Foolish Four as described in The Motley Fool Investment Guide. That research resulted in another article published in the March/April 1999 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal titled "Mining Fool's Gold."4

![]() McQueen and Thorley included a full explanation of the potential pitfalls of data mining and they conducted out of sample tests on the Foolish Four. The Professors reasoned that data mining can be detected by the complexity of the trading rule, the lack of a coherent story or theory, the performance of out-of-sample tests, and the adjustment of returns for risk, transaction costs, and taxes. Additionally, they argued that the Foolish Four and Dow Ten trading rules have become popular enough to impact stock prices at the turn of the year.

McQueen and Thorley included a full explanation of the potential pitfalls of data mining and they conducted out of sample tests on the Foolish Four. The Professors reasoned that data mining can be detected by the complexity of the trading rule, the lack of a coherent story or theory, the performance of out-of-sample tests, and the adjustment of returns for risk, transaction costs, and taxes. Additionally, they argued that the Foolish Four and Dow Ten trading rules have become popular enough to impact stock prices at the turn of the year.

![]() In defense of the Fools, several disclosures were at least made in The Motley Fool Investment Guide and on the web site. In their Foolish Four report dated August 7, 1998, they disclosed that returns were lower when rebalancing occurred in months other than January. Additionally, the return figure from a twenty year period was used many times, but they did at least mention that they researched the numbers back to 1961 and for the longer time period, the returns were lower. On the other hand, once it is disclosed that a longer period of time was studied, continuing to cite the stronger shorter term numbers and basing arguments on that data certainly can be viewed as suspect. Disclosing and focusing on longer term results tends to increase the credibility of a data miner's argument.

In defense of the Fools, several disclosures were at least made in The Motley Fool Investment Guide and on the web site. In their Foolish Four report dated August 7, 1998, they disclosed that returns were lower when rebalancing occurred in months other than January. Additionally, the return figure from a twenty year period was used many times, but they did at least mention that they researched the numbers back to 1961 and for the longer time period, the returns were lower. On the other hand, once it is disclosed that a longer period of time was studied, continuing to cite the stronger shorter term numbers and basing arguments on that data certainly can be viewed as suspect. Disclosing and focusing on longer term results tends to increase the credibility of a data miner's argument.

![]() Jason Zweig summarized in Money magazine in 1999 “In short, the Foolish Four is investment hogwash in its purest form.”5 Shortly thereafter, in December 2000, The Motley Fool announced that they no longer advocated the "Foolish Four" stock strategy and offered further rational in “Re-thinking the Foolish Four” after years of recommending a strategy via their web site and books.6 Later, in 2003, Jason Zweig called the Foolish Four “one of the most cockamamie stock-picking formulas ever concocted” in the revised edition of The Intelligent Investor.

Jason Zweig summarized in Money magazine in 1999 “In short, the Foolish Four is investment hogwash in its purest form.”5 Shortly thereafter, in December 2000, The Motley Fool announced that they no longer advocated the "Foolish Four" stock strategy and offered further rational in “Re-thinking the Foolish Four” after years of recommending a strategy via their web site and books.6 Later, in 2003, Jason Zweig called the Foolish Four “one of the most cockamamie stock-picking formulas ever concocted” in the revised edition of The Intelligent Investor.

![]() Perhaps the greatest cause for concern with the Dow Dividend strategies is the central assumption inherent in these strategies. That is, the assumption that the future will be like the past. Unfortunately, past experiences with disappearing anomalies, the impact of the billions of dollars already invested according to the strategies, and the inconsistent performance of the Dow strategies over significant sub-periods imply that assuming outperformance can be a dangerous assumption. The irony is that the strategy is based on the idea that unpopular stocks outperform. Yet, given the publicity of the Dow strategies, the Dow Dogs at some point could have been just the opposite (popular).

Perhaps the greatest cause for concern with the Dow Dividend strategies is the central assumption inherent in these strategies. That is, the assumption that the future will be like the past. Unfortunately, past experiences with disappearing anomalies, the impact of the billions of dollars already invested according to the strategies, and the inconsistent performance of the Dow strategies over significant sub-periods imply that assuming outperformance can be a dangerous assumption. The irony is that the strategy is based on the idea that unpopular stocks outperform. Yet, given the publicity of the Dow strategies, the Dow Dogs at some point could have been just the opposite (popular).

![]() While its clearly possible that the Dow-10 (and derivative strategies) will outperform in the future, its apparent that some investors in the past had overly optimistic expectations (based on rear-view mirror, back-tested returns for specific time periods) and may not have accounted for the added risk, transactions, and tax costs inherent in the strategy. The strategy's consistency with other value approaches is certainly appealing, but current and future funds committed to the strategies may end up reducing or eliminating any future outperformance.

While its clearly possible that the Dow-10 (and derivative strategies) will outperform in the future, its apparent that some investors in the past had overly optimistic expectations (based on rear-view mirror, back-tested returns for specific time periods) and may not have accounted for the added risk, transactions, and tax costs inherent in the strategy. The strategy's consistency with other value approaches is certainly appealing, but current and future funds committed to the strategies may end up reducing or eliminating any future outperformance.

People are coming to us all the time with trading strategies that reportedly make very large excess returns . . . But the vast majority of the things that people discover by taking standard mathematical tools and sifting through a vast amount of data are statistical artifacts.

David Shaw7

![]() Ted Aronson commented in 1999 that the market is "nearly totally efficient" and that "You're fooling yourself if you think you'll outguess the other guy by more than about 51% or 52% of the time."8 Aronson believes that investors searching for market inefficiencies have reduced the potential to profit from those anomalies to the equivalent of transactions costs. If that is the case, minimizing transactions costs is critical in attempting to beat the market.

Ted Aronson commented in 1999 that the market is "nearly totally efficient" and that "You're fooling yourself if you think you'll outguess the other guy by more than about 51% or 52% of the time."8 Aronson believes that investors searching for market inefficiencies have reduced the potential to profit from those anomalies to the equivalent of transactions costs. If that is the case, minimizing transactions costs is critical in attempting to beat the market.

![]() There have been many serious and robust attempts to clarify the impact of data mining risks regarding stock market anomalies and factor research. In a 2017 working paper, researchers using a century of data on accounting based return anomalies concluded that most are “spurious.”9

There have been many serious and robust attempts to clarify the impact of data mining risks regarding stock market anomalies and factor research. In a 2017 working paper, researchers using a century of data on accounting based return anomalies concluded that most are “spurious.”9

![]() Rob Arnott, Campbell Harvey, and Harry Markowitz suggested in a 2018 paper a protocol of over 20 items to help avoid the problems inherent in data mining. They include before, during, and after researching activities like tracking data, not ignoring costs and fees, as well as many acknowledgements.10 In the same article the authors used data mining to search for the strategy that would have produced the strongest returns based on the letters in stocks’ ticker symbols. They determined that from 1963 to 2015, buying stocks with an “s” as the third letter and shorting stocks with tickers that have “u” as the third letter would have resulted in significant outperformance. Of course, there is no logical reason for that, which highlights the point that simply data mining without a purpose doesn’t necessarily provide anything meaningful, since it may just be a random result.

Rob Arnott, Campbell Harvey, and Harry Markowitz suggested in a 2018 paper a protocol of over 20 items to help avoid the problems inherent in data mining. They include before, during, and after researching activities like tracking data, not ignoring costs and fees, as well as many acknowledgements.10 In the same article the authors used data mining to search for the strategy that would have produced the strongest returns based on the letters in stocks’ ticker symbols. They determined that from 1963 to 2015, buying stocks with an “s” as the third letter and shorting stocks with tickers that have “u” as the third letter would have resulted in significant outperformance. Of course, there is no logical reason for that, which highlights the point that simply data mining without a purpose doesn’t necessarily provide anything meaningful, since it may just be a random result.

![]() In the end, do we ever really know for sure what strategies will outperform in the future? Opinions on that question definitely vary, but the standard disclaimer applies as always. Keep in mind, that the phrase "past performance is no guarantee of future performance" is nothing more than a legal disclaimer. The phrase "past performance may be no indication of future performance" is a more appropriate description in some cases.

In the end, do we ever really know for sure what strategies will outperform in the future? Opinions on that question definitely vary, but the standard disclaimer applies as always. Keep in mind, that the phrase "past performance is no guarantee of future performance" is nothing more than a legal disclaimer. The phrase "past performance may be no indication of future performance" is a more appropriate description in some cases.

![]() I am offering the online chapters of The Peaceful Investor using "The Honor System." If you don't plan to purchase a version of the book, yet you think it was worth your time and you learned a significant amount, you can tip or compensate me in a number of ways. This will probably not be tax deductible for you, but I will report and pay taxes on any payments.

I am offering the online chapters of The Peaceful Investor using "The Honor System." If you don't plan to purchase a version of the book, yet you think it was worth your time and you learned a significant amount, you can tip or compensate me in a number of ways. This will probably not be tax deductible for you, but I will report and pay taxes on any payments.