Table of Contents and Launch Site

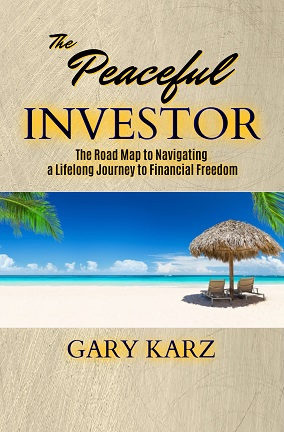

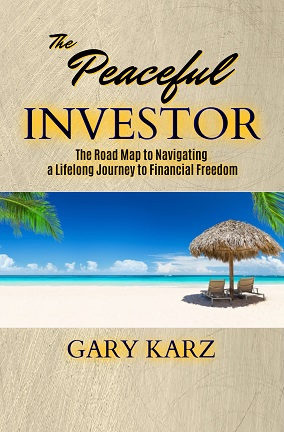

Amazon

I am offering this material using "The Honor System." Tip options at the bottom of the page.

Which of the following do you think is the best long term investment?

Bonds/CDs, Cash, Gold, Stocks, or Real Estate

![]() Some might be surprised to learn that there are multiple reasons why real estate is arguably the best long term investment for many investors. Real estate is one the most interesting asset classes and can offer high returns and relatively low correlations with other major asset classes, which can make real estate a valuable diversifier. Real estate investments often yield more in income than stocks pay in dividends, which can be more attractive to investors seeking current income, and the income can also provide some cushion during bear markets.

Some might be surprised to learn that there are multiple reasons why real estate is arguably the best long term investment for many investors. Real estate is one the most interesting asset classes and can offer high returns and relatively low correlations with other major asset classes, which can make real estate a valuable diversifier. Real estate investments often yield more in income than stocks pay in dividends, which can be more attractive to investors seeking current income, and the income can also provide some cushion during bear markets.

![]() Investors can diversify within real estate by location, economic region, and property type. Brad Case has suggested that the correlation between Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and the stock market has always been relatively low because REIT returns are driven by the real estate market cycle, while returns for most other equities is often driven by the business cycle.1

Investors can diversify within real estate by location, economic region, and property type. Brad Case has suggested that the correlation between Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and the stock market has always been relatively low because REIT returns are driven by the real estate market cycle, while returns for most other equities is often driven by the business cycle.1

![]() In an era when stocks are often considered the primary asset class for many long-term investors, REITs have earned the right to join the debate about the best investment option. Land, farmland, and homes have been stores of value for thousands of years. With the proliferation of REITs in recent decades we now have data supporting the argument that REITs have had returns comparable to, and according to some data, stronger than stocks and other asset classes over extended periods.

In an era when stocks are often considered the primary asset class for many long-term investors, REITs have earned the right to join the debate about the best investment option. Land, farmland, and homes have been stores of value for thousands of years. With the proliferation of REITs in recent decades we now have data supporting the argument that REITs have had returns comparable to, and according to some data, stronger than stocks and other asset classes over extended periods.

![]() In my experience, many investors are more attracted to, and are more comfortable with, real estate relative to other investments. Some have also suggested that some forms of investment real estate can be viewed as a hybrid between bonds and stocks. For instance, if you own a property that is leased long-term to a large organization, arguably the rent can be viewed as a bond-like income stream dependent on the credit quality of that organization. From that perspective, risk-averse investors seeking higher returns than offered by bonds might consider real estate before stocks.

In my experience, many investors are more attracted to, and are more comfortable with, real estate relative to other investments. Some have also suggested that some forms of investment real estate can be viewed as a hybrid between bonds and stocks. For instance, if you own a property that is leased long-term to a large organization, arguably the rent can be viewed as a bond-like income stream dependent on the credit quality of that organization. From that perspective, risk-averse investors seeking higher returns than offered by bonds might consider real estate before stocks.

![]() In fact, recent surveys have found that more people on average choose real estate as a best long term investment, ahead of stocks. Bankrate.com conducts a survey annually. In their 2019 survey, they asked "For money you wouldn't need for more than 10 years, which ONE of the following do you think would be the best way to invest it?" 31 percent chose Real Estate, followed by stocks at 20%, cash investments (savings accounts and CDs) at 19 percent, gold and other precious metals at 11 percent, and Bonds at 7 percent.2 The question was slightly different in prior years ("What is the best way to invest money you don't need for 10 years or more?") and Real Estate was the top choice in the 2015 to 2017 surveys3 although in 2018, 32% chose the stock market, making it the top choice.4

In fact, recent surveys have found that more people on average choose real estate as a best long term investment, ahead of stocks. Bankrate.com conducts a survey annually. In their 2019 survey, they asked "For money you wouldn't need for more than 10 years, which ONE of the following do you think would be the best way to invest it?" 31 percent chose Real Estate, followed by stocks at 20%, cash investments (savings accounts and CDs) at 19 percent, gold and other precious metals at 11 percent, and Bonds at 7 percent.2 The question was slightly different in prior years ("What is the best way to invest money you don't need for 10 years or more?") and Real Estate was the top choice in the 2015 to 2017 surveys3 although in 2018, 32% chose the stock market, making it the top choice.4

![]() Gallup conducts a similar survey annually and they have had similar results recently.5 Gallup uses the term savings accounts/CDs (instead of cash investments) and has in the past grouped stocks with mutual funds (which doesn't make much sense since mutual funds can invest in all of the categories). The primary result was real estate was chosen first with 35% (winning for the sixth straight year) with stocks/mutual funds in second at 27%, followed by savings and gold.6 Gallup noted that real estate may rank ahead of stocks because more American families own their own homes than own stocks (roughly 63% versus 55%).7

Gallup conducts a similar survey annually and they have had similar results recently.5 Gallup uses the term savings accounts/CDs (instead of cash investments) and has in the past grouped stocks with mutual funds (which doesn't make much sense since mutual funds can invest in all of the categories). The primary result was real estate was chosen first with 35% (winning for the sixth straight year) with stocks/mutual funds in second at 27%, followed by savings and gold.6 Gallup noted that real estate may rank ahead of stocks because more American families own their own homes than own stocks (roughly 63% versus 55%).7

![]() The results of these surveys can be very sensitive to the specific language, for instance Gallup notes that another 2018 survey had only 19% choosing real estate first when the language stated to exclude the respondents primary home from the real estate category.8 But the survey results also varied substantially in the wake of the global financial crisis. From 2008 and 2010, Americans were as likely to choose savings accounts or CDs as the best long-term investment as they were to name stocks or real estate, and when Gallup added gold as an option in 2011, it topped the list for several years before fading recently. 14% chose gold as the best investment in 2019 down from 34% in 2011 (more on gold in Chapter 18).

The results of these surveys can be very sensitive to the specific language, for instance Gallup notes that another 2018 survey had only 19% choosing real estate first when the language stated to exclude the respondents primary home from the real estate category.8 But the survey results also varied substantially in the wake of the global financial crisis. From 2008 and 2010, Americans were as likely to choose savings accounts or CDs as the best long-term investment as they were to name stocks or real estate, and when Gallup added gold as an option in 2011, it topped the list for several years before fading recently. 14% chose gold as the best investment in 2019 down from 34% in 2011 (more on gold in Chapter 18).

![]() Before discussing the historical returns data it’s important to clarify some real estate terms. There are two types of land. Unused land in undeveloped areas has no income and may have costs to maintain (and/or property taxes). So as I mentioned in chapter 13, I consider unused land in most cases to be more like a commodity than an investment. Farmland, or leased land, however is a legitimate investment because it has cash flow.

Before discussing the historical returns data it’s important to clarify some real estate terms. There are two types of land. Unused land in undeveloped areas has no income and may have costs to maintain (and/or property taxes). So as I mentioned in chapter 13, I consider unused land in most cases to be more like a commodity than an investment. Farmland, or leased land, however is a legitimate investment because it has cash flow.

![]() Homes can also be viewed in several ways. Buying a home that is vacant also may have costs for upkeep and property taxes. Lacking positive cash flow, unrented homes in the U.S. have historically not appreciated significantly more than inflation. But owning homes for the purpose of renting is a legitimate investment. Historically buying individual homes to rent (and resell) was a so-called mom-and-pop business, but following the global financial crisis a new industry has evolved that offers an opportunity to buy a diversified portfolio of professionally managed rental homes. I'll elaborate later in the chapter on that option along with recent research suggesting that investing in homes has had similar returns to stocks in many countries.

Homes can also be viewed in several ways. Buying a home that is vacant also may have costs for upkeep and property taxes. Lacking positive cash flow, unrented homes in the U.S. have historically not appreciated significantly more than inflation. But owning homes for the purpose of renting is a legitimate investment. Historically buying individual homes to rent (and resell) was a so-called mom-and-pop business, but following the global financial crisis a new industry has evolved that offers an opportunity to buy a diversified portfolio of professionally managed rental homes. I'll elaborate later in the chapter on that option along with recent research suggesting that investing in homes has had similar returns to stocks in many countries.

![]() Institutional investors and investors with substantial capital traditionally buy income producing real estate (both directly and through various types of funds). They can include multi-family properties like apartment buildings, retail and commercial properties, office and other buildings, or storage facilities and warehouses. While the market for real estate properties can be less efficient than publicly traded securities, making money buying and selling, or owning to rent, can involve extensive amounts of time and effort, in addition to capital. A potential disadvantage of owning real estate directly for some investors is being a landlord and having to manage the properties, although many of those functions can be outsourced (at a cost). Real estate tends to have high transactions costs, private transactions can suffer from a lack of publicly available audited information, and transactions can be complex (city, state, and federal laws can vary).

Institutional investors and investors with substantial capital traditionally buy income producing real estate (both directly and through various types of funds). They can include multi-family properties like apartment buildings, retail and commercial properties, office and other buildings, or storage facilities and warehouses. While the market for real estate properties can be less efficient than publicly traded securities, making money buying and selling, or owning to rent, can involve extensive amounts of time and effort, in addition to capital. A potential disadvantage of owning real estate directly for some investors is being a landlord and having to manage the properties, although many of those functions can be outsourced (at a cost). Real estate tends to have high transactions costs, private transactions can suffer from a lack of publicly available audited information, and transactions can be complex (city, state, and federal laws can vary).

![]() Individual investors that invest in real estate can buy one property at a time privately, but that can be risky because each property is unique and neighborhoods can become more or less attractive over time. Plus many buy with leverage (by borrowing to make purchases) which can increase volatility of returns. Investors also have the option to invest in partnerships, or other groups. The other option for individual investors is to buy shares in a REIT, or a fund of REITs.

Individual investors that invest in real estate can buy one property at a time privately, but that can be risky because each property is unique and neighborhoods can become more or less attractive over time. Plus many buy with leverage (by borrowing to make purchases) which can increase volatility of returns. Investors also have the option to invest in partnerships, or other groups. The other option for individual investors is to buy shares in a REIT, or a fund of REITs.

![]() From 2010 to 2016 the market capitalization of U.S. REITs grew about 150%, while REITs outside the U.S. grew by about 100%.9 The market capitalization of REITs passed $1 trillion in 2016 and there were 226 publicly traded REITs as of 2018.10 REITs have been steadily increasing their holdings as a percentage of properties in recent decades and it’s likely that trend will continue. Alexandra Thompson recently estimated via reit.com that U.S. REITS held over 20% of the investment grade commercial properties, up from less than 5% prior to 2003.11 More than 35 countries now have REITs.

From 2010 to 2016 the market capitalization of U.S. REITs grew about 150%, while REITs outside the U.S. grew by about 100%.9 The market capitalization of REITs passed $1 trillion in 2016 and there were 226 publicly traded REITs as of 2018.10 REITs have been steadily increasing their holdings as a percentage of properties in recent decades and it’s likely that trend will continue. Alexandra Thompson recently estimated via reit.com that U.S. REITS held over 20% of the investment grade commercial properties, up from less than 5% prior to 2003.11 More than 35 countries now have REITs.

![]() U.S. REITs are technically treated as corporations for tax purposes, however, the income is taxed only at the shareholder level if certain requirements are satisfied. REIT requirements typically include management by a board of directors, fully transferable shares, a minimum of 100 shareholders, at least 75 percent of income must come from real estate, and they must pay dividends of at least 90% of the REIT's taxable income. Another potential advantage of REITS is that part of the dividend is treated as return of capital, which can lower the tax bite on dividends. Some have argued that the Trump "Tax Cuts and Jobs Act" signed in 2017 offers additional advantages for U.S. REIT investors relative to direct real estate ownership.12 A provision of the tax law allows most individuals deductions on REIT income, but the cap on itemized deductions of state and local taxes (usually including property tax) may disadvantage direct real estate ownership.

U.S. REITs are technically treated as corporations for tax purposes, however, the income is taxed only at the shareholder level if certain requirements are satisfied. REIT requirements typically include management by a board of directors, fully transferable shares, a minimum of 100 shareholders, at least 75 percent of income must come from real estate, and they must pay dividends of at least 90% of the REIT's taxable income. Another potential advantage of REITS is that part of the dividend is treated as return of capital, which can lower the tax bite on dividends. Some have argued that the Trump "Tax Cuts and Jobs Act" signed in 2017 offers additional advantages for U.S. REIT investors relative to direct real estate ownership.12 A provision of the tax law allows most individuals deductions on REIT income, but the cap on itemized deductions of state and local taxes (usually including property tax) may disadvantage direct real estate ownership.

![]() Nontraded REITs are those that are not listed in the securities markets and I view them with some suspicion. One reason they may choose not to list publicly could be because the managers don’t want to be subjected to the listing requirements, as well as the scrutiny of researchers and analysts. Sophisticated investors with their own research resources may have reasons to investigate and invest in nontraded REITs, but most individual investors don't have those resources and skills. Most investors in REITs should be long-term investors that trade infrequently, but the ability to buy and sell in the public market is an important and valuable option. Any commissions embedded in newly issued nontraded REITs increase their disadvantage relative to public REITs.

Nontraded REITs are those that are not listed in the securities markets and I view them with some suspicion. One reason they may choose not to list publicly could be because the managers don’t want to be subjected to the listing requirements, as well as the scrutiny of researchers and analysts. Sophisticated investors with their own research resources may have reasons to investigate and invest in nontraded REITs, but most individual investors don't have those resources and skills. Most investors in REITs should be long-term investors that trade infrequently, but the ability to buy and sell in the public market is an important and valuable option. Any commissions embedded in newly issued nontraded REITs increase their disadvantage relative to public REITs.

![]() Numerous studies have found that over several decades, REIT returns beat private real estate funds and other alternatives.13 Recent data finds that pension funds have less than 1% allocated to REITs, and pension funds, endowments and foundations have less than one fifth of their allocation to real estate in REITs.14 Listed REITs have had high returns and relatively low fees (typically half of those for private real estate) and they have generally outperformed direct and private real estate investments in portfolios of institutional investor.

Numerous studies have found that over several decades, REIT returns beat private real estate funds and other alternatives.13 Recent data finds that pension funds have less than 1% allocated to REITs, and pension funds, endowments and foundations have less than one fifth of their allocation to real estate in REITs.14 Listed REITs have had high returns and relatively low fees (typically half of those for private real estate) and they have generally outperformed direct and private real estate investments in portfolios of institutional investor.

![]() In 2011, Morningstar found that for the 20 year period January 1989—December 2009, REITs were the top performer with a compound net total return of 9.3% versus 4.4% for private core funds. They also noted the fact that REIT fees and expenses averaged one-half to one-fourth of private equity real estate fees (which I would suggest is not unrelated to the underperformance). They concluded "Publicly traded equity REITs have outperformed core, value-added, and opportunistic funds consistently over the long term, experienced stronger bull markets, recovered faster from downturns, and had lower fees and expenses on average compared with private equity real estate funds."15

In 2011, Morningstar found that for the 20 year period January 1989—December 2009, REITs were the top performer with a compound net total return of 9.3% versus 4.4% for private core funds. They also noted the fact that REIT fees and expenses averaged one-half to one-fourth of private equity real estate fees (which I would suggest is not unrelated to the underperformance). They concluded "Publicly traded equity REITs have outperformed core, value-added, and opportunistic funds consistently over the long term, experienced stronger bull markets, recovered faster from downturns, and had lower fees and expenses on average compared with private equity real estate funds."15

![]() Green Street Advisors commented in 2014 that REITs behave like real estate over extended time periods and deliver superior returns relative to what pension funds achieve via private real estate investing. They concluded "While this evidence has been accumulating for quite some time, an exhaustive new study by CEM Benchmarking of real-world investment performance should serve as the nail in the coffin of the crowd that eschews listed REITs." They noted at the time that listed REITs had only a 0.6% allocation, while private real estate had captured a 3.3% share.16

Green Street Advisors commented in 2014 that REITs behave like real estate over extended time periods and deliver superior returns relative to what pension funds achieve via private real estate investing. They concluded "While this evidence has been accumulating for quite some time, an exhaustive new study by CEM Benchmarking of real-world investment performance should serve as the nail in the coffin of the crowd that eschews listed REITs." They noted at the time that listed REITs had only a 0.6% allocation, while private real estate had captured a 3.3% share.16

![]() Green Street Advisors found that on average, the return produced by nontraded REITs lagged their publicly-traded peers that specialize in the same kind of property by 3.6% per year. Non-traded REITs were even compared to Neanderthals (inferior to Homo sapiens, yet they managed to co-exist with them for thousands of years before going extinct). The average annualized returns for nontraded REITs were 10.9% for the 34 companies examined, compared to 14.5% for listed REITs.17 Cambridge Associates reported in 2017 that private equity real estate funds have underperformed listed equity REITs by 3.9% per year over the past 25 years.18

Green Street Advisors found that on average, the return produced by nontraded REITs lagged their publicly-traded peers that specialize in the same kind of property by 3.6% per year. Non-traded REITs were even compared to Neanderthals (inferior to Homo sapiens, yet they managed to co-exist with them for thousands of years before going extinct). The average annualized returns for nontraded REITs were 10.9% for the 34 companies examined, compared to 14.5% for listed REITs.17 Cambridge Associates reported in 2017 that private equity real estate funds have underperformed listed equity REITs by 3.9% per year over the past 25 years.18

![]() Comparing REITs to other assets classes, several data sources show equity REITs (which exclude mortgage REITs) outperforming stocks over recent decades. From January 1978 through May 2017 the Dow Jones Select REIT Index returned 12.2% annually versus 11.7% for the S&P 500 Index and 7.1% for five-year Treasury bonds.19

Comparing REITs to other assets classes, several data sources show equity REITs (which exclude mortgage REITs) outperforming stocks over recent decades. From January 1978 through May 2017 the Dow Jones Select REIT Index returned 12.2% annually versus 11.7% for the S&P 500 Index and 7.1% for five-year Treasury bonds.19

![]() Critics of REITs note that they have been volatile in prior periods. Vanguard's VNQ REIT ETF had gains of 33% in 2006 and 30% in 2009, but lost 16% and 37% in 2007 and 2008. Ishares IFGL (an international REIT fund) lost 52% in 2008, but gained 42% in 2009. In 1974-75 REIT prices were more than cut in half and following the tax reform act of 1986, REITs lost roughly one third of their value (1987-91). Another concern with REITs is that historical correlations with small stocks have been higher than other asset classes, which lessens the diversification benefits of investing in real estate.

Critics of REITs note that they have been volatile in prior periods. Vanguard's VNQ REIT ETF had gains of 33% in 2006 and 30% in 2009, but lost 16% and 37% in 2007 and 2008. Ishares IFGL (an international REIT fund) lost 52% in 2008, but gained 42% in 2009. In 1974-75 REIT prices were more than cut in half and following the tax reform act of 1986, REITs lost roughly one third of their value (1987-91). Another concern with REITs is that historical correlations with small stocks have been higher than other asset classes, which lessens the diversification benefits of investing in real estate.

![]() Jeremy Siegel noted in Stocks for the Long Run that the Dow Jones REIT Index peaked in 2008, and REITs lost on average an astounding two-thirds of their value over a ten week period and “fell a total of 75 percent by the time the bear market ended in March 2009." Curiously though, Siegel doesn’t mention REITs long-term (out)performance relative to stocks.

Jeremy Siegel noted in Stocks for the Long Run that the Dow Jones REIT Index peaked in 2008, and REITs lost on average an astounding two-thirds of their value over a ten week period and “fell a total of 75 percent by the time the bear market ended in March 2009." Curiously though, Siegel doesn’t mention REITs long-term (out)performance relative to stocks.

![]() Brad Case pointed out in April of 2016 that from the end of 1978 through the end of the first quarter of 2016 REIT returns outpaced stock returns during 82% of the available 30-year periods and the FTSE NAREIT All Equity REITs has outperformed the Russell 3000 Index 100% the time for periods of at least 32 years.20

Brad Case pointed out in April of 2016 that from the end of 1978 through the end of the first quarter of 2016 REIT returns outpaced stock returns during 82% of the available 30-year periods and the FTSE NAREIT All Equity REITs has outperformed the Russell 3000 Index 100% the time for periods of at least 32 years.20

![]() Craig Israelsen in “Fear of Falling” in the December 2017 issue of Financial Planning compared U.S. REIT performance (Dow Jones U.S. Select REIT index) from 1970 through 2016 to stocks and other asset classes. The REIT index had annualized returns averaging 11.94% versus 11.02% for the small cap (Russell 2000) and 10.31% for the large cap (S&P 500) indexes. REITs were also arguably less risky on one measure he calculated (% of years with positive returns). The REIT index had gains in 83% of the years versus 81% for large caps and 70% for small caps.21

Craig Israelsen in “Fear of Falling” in the December 2017 issue of Financial Planning compared U.S. REIT performance (Dow Jones U.S. Select REIT index) from 1970 through 2016 to stocks and other asset classes. The REIT index had annualized returns averaging 11.94% versus 11.02% for the small cap (Russell 2000) and 10.31% for the large cap (S&P 500) indexes. REITs were also arguably less risky on one measure he calculated (% of years with positive returns). The REIT index had gains in 83% of the years versus 81% for large caps and 70% for small caps.21

![]() Ralph Block is the author of Investing in REITs: Real Estate Investment Trusts 4th edition (2011) and he cited returns data for several decades starting with the creation of REITs in the 1960s, referencing Goldman Sachs’ “The REIT Investment Summary” (1996). There were apparently ten REITs of significant size in the 1960s ranging from $11 million to $44 million (for REIT of America). According to that data from 1963-1970 Equity REITs returned 11.5% versus 6.7% for the S&P 500. According to the same report, in the 1970s equity REITS returned 12.9% versus 5.8% for S&P.

Ralph Block is the author of Investing in REITs: Real Estate Investment Trusts 4th edition (2011) and he cited returns data for several decades starting with the creation of REITs in the 1960s, referencing Goldman Sachs’ “The REIT Investment Summary” (1996). There were apparently ten REITs of significant size in the 1960s ranging from $11 million to $44 million (for REIT of America). According to that data from 1963-1970 Equity REITs returned 11.5% versus 6.7% for the S&P 500. According to the same report, in the 1970s equity REITS returned 12.9% versus 5.8% for S&P.

![]() Ronald Doeswijk, Trevin Lam, and Laurens Swinkels recently published research citing global data from 1960-2015 that also finds real estate outperformed global stocks (by about 1% annually). Their data suggests the global market portfolio return for the period was 8.3%, while equities returned almost 9.5% and real estate returned almost 10.5%, with inflation at 3.8%.22

Ronald Doeswijk, Trevin Lam, and Laurens Swinkels recently published research citing global data from 1960-2015 that also finds real estate outperformed global stocks (by about 1% annually). Their data suggests the global market portfolio return for the period was 8.3%, while equities returned almost 9.5% and real estate returned almost 10.5%, with inflation at 3.8%.22

![]() Many believe that REITs can lose significant value when interest rates rise (as in early 2018). But according to Calvin Schnure at the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts, since 1995 (through 2015) there were 16 periods of significant interest rate increases and REITs were positive for 12 of those periods.23 In some short (like 2017) and mid-term periods (like the 1980s) REITs have underperformed, but a large percentage of the long-term data supports the conclusion that equity REITs have outperformed stocks since their introduction in the 1960s.

Many believe that REITs can lose significant value when interest rates rise (as in early 2018). But according to Calvin Schnure at the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts, since 1995 (through 2015) there were 16 periods of significant interest rate increases and REITs were positive for 12 of those periods.23 In some short (like 2017) and mid-term periods (like the 1980s) REITs have underperformed, but a large percentage of the long-term data supports the conclusion that equity REITs have outperformed stocks since their introduction in the 1960s.

Rental Home Investing

From an investment perspective, I think rental home investments may be particularly interesting for individuals that don't own homes, especially those that are planning to buy a home in the future. Those individuals could attempt to hedge against rising home prices by using their down payment savings to buy a stake in a rental homes (Robert Shiller has suggested the use of real estate futures in various markets as another option for hedging housing price movement).

![]() Many people blamed “Wall Street” for the global financial crisis (while others blame the government, although most blame multiple parties). So there is some irony that "Wall Street" (with some government involvement) contributed to the recovery by creating what eventually evolved into publicly traded rental homes firms. Arguably, this new asset class helped the real estate market recover, gave the construction and home repair industries a boost, along with the economy, and the home rental firms may even help stabilize real estate prices in the future (although there have been plenty of reports of renters complaining about difficulty getting timely repairs from corporate owners).24

Many people blamed “Wall Street” for the global financial crisis (while others blame the government, although most blame multiple parties). So there is some irony that "Wall Street" (with some government involvement) contributed to the recovery by creating what eventually evolved into publicly traded rental homes firms. Arguably, this new asset class helped the real estate market recover, gave the construction and home repair industries a boost, along with the economy, and the home rental firms may even help stabilize real estate prices in the future (although there have been plenty of reports of renters complaining about difficulty getting timely repairs from corporate owners).24

![]() The asset class has the potential to smooth out real estate price moves, although some argue that the short-term oriented investors may move in tandem, thus destabilizing prices. If prices rise too much relative to rental rates, rental homes can be sold, thus adding to the supply and potentially reducing prices. If prices drop relative to rents, more homes can be converted to rentals, reducing the supply and potentially increasing home prices.

The asset class has the potential to smooth out real estate price moves, although some argue that the short-term oriented investors may move in tandem, thus destabilizing prices. If prices rise too much relative to rental rates, rental homes can be sold, thus adding to the supply and potentially reducing prices. If prices drop relative to rents, more homes can be converted to rentals, reducing the supply and potentially increasing home prices.

![]() Warren Buffett commented in 2012 "I'd Buy Up 'A Couple Hundred Thousand' Single-Family Homes If I Could" and that comment may have encouraged others to enter the field.25 In a 2013 article about the developing asset class, Paul Saylor described the rental housing business as “the best new opportunity in pension fund investing in real estate in a very long time."26

Warren Buffett commented in 2012 "I'd Buy Up 'A Couple Hundred Thousand' Single-Family Homes If I Could" and that comment may have encouraged others to enter the field.25 In a 2013 article about the developing asset class, Paul Saylor described the rental housing business as “the best new opportunity in pension fund investing in real estate in a very long time."26

![]() Rental home REITs have evolved in the last decade and there are now two multi-billion dollar U.S. listed REITs that give investors the opportunity to buy a package of rental homes. At the end of the third quarter of 2019 American Homes 4 Rent (AMH) owned over 52,000 single-family in 22 states. The firm was founded by Public Storage billionaire Wayne Hughes and became a public company in 2013. AMH had a stock market capitalization around $8 billion in late 2019 and is included in the broad REIT market index fund VNQ. The Wall Street Journal noted on January 3, 2019 that AMH has even been building houses to rent throughout the Southeast.27 By building houses, they can avoids sales commissions and renovation costs and outfit homes with its preferred fixtures and finishes at the onset, while typically charging higher rents than for its older homes. The new homes should also have lower maintenance costs. Canadian firm Tricon Capital Group started adding new homes recently to its existing 17,000 U.S. rental homes and has said it intends to acquire as many as 12,000 more single-family properties.

Rental home REITs have evolved in the last decade and there are now two multi-billion dollar U.S. listed REITs that give investors the opportunity to buy a package of rental homes. At the end of the third quarter of 2019 American Homes 4 Rent (AMH) owned over 52,000 single-family in 22 states. The firm was founded by Public Storage billionaire Wayne Hughes and became a public company in 2013. AMH had a stock market capitalization around $8 billion in late 2019 and is included in the broad REIT market index fund VNQ. The Wall Street Journal noted on January 3, 2019 that AMH has even been building houses to rent throughout the Southeast.27 By building houses, they can avoids sales commissions and renovation costs and outfit homes with its preferred fixtures and finishes at the onset, while typically charging higher rents than for its older homes. The new homes should also have lower maintenance costs. Canadian firm Tricon Capital Group started adding new homes recently to its existing 17,000 U.S. rental homes and has said it intends to acquire as many as 12,000 more single-family properties.

![]() Invitation Homes (INVH) went public at the start of 2017 and merged with Starwood Waypoint. In December 2019 its stock market capitalization was over $16 billion. INVH owns over 82,000 homes in 17 markets across the country. I wrote on my website in 2013 that "I wouldn't be surprised to see a public firm eventually holding over 100,000 homes" and that threshold has almost been reached by INVH.28 There are several other smaller firms, some of which have equity home ownership along with mortgages or other debt securities related to rental homes.

Invitation Homes (INVH) went public at the start of 2017 and merged with Starwood Waypoint. In December 2019 its stock market capitalization was over $16 billion. INVH owns over 82,000 homes in 17 markets across the country. I wrote on my website in 2013 that "I wouldn't be surprised to see a public firm eventually holding over 100,000 homes" and that threshold has almost been reached by INVH.28 There are several other smaller firms, some of which have equity home ownership along with mortgages or other debt securities related to rental homes.

![]() Credit Suisse’ 2012 Global Investment Returns Yearbook included commentary citing housing data for more than a century, including data from Neil Monnery (2011), who studied house prices in the U.K., the U.S., France, Holland, Norway, Germany and Australia.29 One study by professors at the London Business School found that housing returned only 1.3 percent per year after inflation from 1900 to 2011, while stocks tended to perform more than four times better. They also compared the long-term capital appreciation of housing to gold’s performance. The best-performing house-price indexes were Australia (2.03% per year) and the United Kingdom (1.33%). The United States (0.09%) was the worst. Norway (0.93%), the Netherlands (0.95%), and France (1.18%) fell in the middle.29

Credit Suisse’ 2012 Global Investment Returns Yearbook included commentary citing housing data for more than a century, including data from Neil Monnery (2011), who studied house prices in the U.K., the U.S., France, Holland, Norway, Germany and Australia.29 One study by professors at the London Business School found that housing returned only 1.3 percent per year after inflation from 1900 to 2011, while stocks tended to perform more than four times better. They also compared the long-term capital appreciation of housing to gold’s performance. The best-performing house-price indexes were Australia (2.03% per year) and the United Kingdom (1.33%). The United States (0.09%) was the worst. Norway (0.93%), the Netherlands (0.95%), and France (1.18%) fell in the middle.29

![]() Homes are costly to maintain and can be difficult and expensive to sell, especially in bad markets. The authors noted that House price indexes are notoriously difficult to interpret, but have at least kept pace with inflation over the long term. Nevertheless, they cautioned that a home is a consumption good, as well as an investment. The attributes of a home are a by-product of its intrinsic utility to those living in the home.

Homes are costly to maintain and can be difficult and expensive to sell, especially in bad markets. The authors noted that House price indexes are notoriously difficult to interpret, but have at least kept pace with inflation over the long term. Nevertheless, they cautioned that a home is a consumption good, as well as an investment. The attributes of a home are a by-product of its intrinsic utility to those living in the home.

![]() According to the 2018 Credit Suisse Yearbook, U.S. homes were the weakest performers among 11 countries rising just 2.2% annually over 118 years, or just 0.3% above inflation.30 But the key is that and many other data sources do not include rental income, or an imputed cost savings for those living in their homes.

According to the 2018 Credit Suisse Yearbook, U.S. homes were the weakest performers among 11 countries rising just 2.2% annually over 118 years, or just 0.3% above inflation.30 But the key is that and many other data sources do not include rental income, or an imputed cost savings for those living in their homes.

![]() Others argue returns on homes have been strong. A widely circulated paper titled "The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870–2015" was eventually published in the August 2019 issue of The Quarterly Journal of Economics. The authors reviewed a new and comprehensive dataset covering total returns for housing as well as equity, bonds, and bills in 16 advanced economies from 1870 to 2015 (Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Rather than looking at just home prices, they estimated home rents using various data sources.

Others argue returns on homes have been strong. A widely circulated paper titled "The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870–2015" was eventually published in the August 2019 issue of The Quarterly Journal of Economics. The authors reviewed a new and comprehensive dataset covering total returns for housing as well as equity, bonds, and bills in 16 advanced economies from 1870 to 2015 (Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Rather than looking at just home prices, they estimated home rents using various data sources.

"The first key finding is that residential real estate, not equity, has been the best long-run investment over the course of modern history. Although returns on housing and equities are similar, the volatility of housing returns is substantially lower."

Òscar Jordà, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, and Alan Taylor31

![]() They came to the conclusion that in many countries residential real estate, not equity, had been the best long-run investment. That finding appears to contradict the assumptions that higher risks should come with higher rewards. They estimated transactions costs at less than 1% (of the annualized return). Individual transactions cost about 7.7% of the property’s value, but turnover tends to be low. More than half of U.S. homeowners had lived in their current home for more than 10 years, and they argued holding periods are similar in the U.K., Australia and the Netherlands. They also estimated that the impact of property taxes would lower the real estate returns by less than 1% relative to equity. They also note that the impact of capital gains taxes complicates the comparison of tax differences between the asset classes and there are also leverage factors to consider.

They came to the conclusion that in many countries residential real estate, not equity, had been the best long-run investment. That finding appears to contradict the assumptions that higher risks should come with higher rewards. They estimated transactions costs at less than 1% (of the annualized return). Individual transactions cost about 7.7% of the property’s value, but turnover tends to be low. More than half of U.S. homeowners had lived in their current home for more than 10 years, and they argued holding periods are similar in the U.K., Australia and the Netherlands. They also estimated that the impact of property taxes would lower the real estate returns by less than 1% relative to equity. They also note that the impact of capital gains taxes complicates the comparison of tax differences between the asset classes and there are also leverage factors to consider.

![]() Those that have purchased a house or other property are likely to be familiar with the appraisal process. Appraisals are usually used to estimate real estate values for loans and other real estate transactions. There are three primary approaches used in valuing or appraising real estate and those investing in real estate should be familiar with some of the commonly used terms. The cost approach, which generally works well for estimating the value of new buildings, involves estimating the cost to build an identical property taking into account land prices, labor, construction materials, and a developer’s profit. The comparative sales approach involves estimating a property's value by comparing it to similar properties recently sold. The complication with this approach is that all properties are unique and adjustments must be made to account for differences in the properties being compared. The income approach involves estimating a property’s value by calculating the present value of future income. The formula for market value equals annual net operating income (NOI) divided by a market capitalization rate that is usually estimated using market factors, or determined from comparable sales. Funds from operations (FFO) is a commonly used term representing funds available for distribution to shareholders, and usually calculated from net income, plus depreciation, less principal payments.

Those that have purchased a house or other property are likely to be familiar with the appraisal process. Appraisals are usually used to estimate real estate values for loans and other real estate transactions. There are three primary approaches used in valuing or appraising real estate and those investing in real estate should be familiar with some of the commonly used terms. The cost approach, which generally works well for estimating the value of new buildings, involves estimating the cost to build an identical property taking into account land prices, labor, construction materials, and a developer’s profit. The comparative sales approach involves estimating a property's value by comparing it to similar properties recently sold. The complication with this approach is that all properties are unique and adjustments must be made to account for differences in the properties being compared. The income approach involves estimating a property’s value by calculating the present value of future income. The formula for market value equals annual net operating income (NOI) divided by a market capitalization rate that is usually estimated using market factors, or determined from comparable sales. Funds from operations (FFO) is a commonly used term representing funds available for distribution to shareholders, and usually calculated from net income, plus depreciation, less principal payments.

What percent of your asset allocation should be in real estate?

![]() Jack Bogle (in Common Sense on Mutual funds) and many others have cited what is often referred to as “The Talmud Portfolio.” I became more curious about the citations while researching REITs for this book since it implies that nearly two thousand years ago, the Rabbis that recorded the Oral Torah provided an early recommendation for diversification, as well as possibly an early recommended asset allocation. The Talmud portfolio refers to a line in Gemara, which is in Aramaic. There are multiple translations into English, one being “Rebbi Yitzchak advises a person to invest his money - one third in land and one third in business, and the remaining third, he should hold in cash.”32

Jack Bogle (in Common Sense on Mutual funds) and many others have cited what is often referred to as “The Talmud Portfolio.” I became more curious about the citations while researching REITs for this book since it implies that nearly two thousand years ago, the Rabbis that recorded the Oral Torah provided an early recommendation for diversification, as well as possibly an early recommended asset allocation. The Talmud portfolio refers to a line in Gemara, which is in Aramaic. There are multiple translations into English, one being “Rebbi Yitzchak advises a person to invest his money - one third in land and one third in business, and the remaining third, he should hold in cash.”32

![]() Another common translation is "Let every man divide his money into three parts, and invest a third in land, a third in business, and a third let him keep by him in reserve.” The translations I found agree that the first third is land, but the second third has also been translated as merchandise, and the final third has also been translated as keeping the money as readily available. The Gemara expands on the Mishnah which discusses the concept of negligence by an unpaid custodian (which is different than a paid custodian that would be more comparable to a modern day advisor). The main theme of the discussion is keeping your money accessible, and about safeguarding money. Later the Gemara discusses the likelihood of thieves checking for money buried underground, or hidden in walls, or above ceiling beams (the Rabbis recognized that changing times and practices require adjusting behavior). You could argue that a modern day version of The Talmud Portfolio could be one third REITs, one third stocks, and one third bonds. The modern versions of these investments can be bought on the public exchanges and are very liquid, which arguably satisfy the recommendation to have your money available.

Another common translation is "Let every man divide his money into three parts, and invest a third in land, a third in business, and a third let him keep by him in reserve.” The translations I found agree that the first third is land, but the second third has also been translated as merchandise, and the final third has also been translated as keeping the money as readily available. The Gemara expands on the Mishnah which discusses the concept of negligence by an unpaid custodian (which is different than a paid custodian that would be more comparable to a modern day advisor). The main theme of the discussion is keeping your money accessible, and about safeguarding money. Later the Gemara discusses the likelihood of thieves checking for money buried underground, or hidden in walls, or above ceiling beams (the Rabbis recognized that changing times and practices require adjusting behavior). You could argue that a modern day version of The Talmud Portfolio could be one third REITs, one third stocks, and one third bonds. The modern versions of these investments can be bought on the public exchanges and are very liquid, which arguably satisfy the recommendation to have your money available.

![]() REITs are usually included in total stock market funds, so investing in a total U.S. stock market usually includes some REITs as a subsector of the stock market. In 2016, S&P Dow Jones Indices and MSCI shifted stock-exchange listed real estate companies from a subcategory of the financial sector to a new real estate sector. REITs represent approximately 3-4% of the market-capitalization of broad U.S. stock funds, which is a valid starting point for a REIT allocation in a diversified portfolio.33 REITs also offer exposure to some segments of the commercial real estate market (data centers and cell tower for instance) that aren’t as easy to access through traditional private real estate investment.

REITs are usually included in total stock market funds, so investing in a total U.S. stock market usually includes some REITs as a subsector of the stock market. In 2016, S&P Dow Jones Indices and MSCI shifted stock-exchange listed real estate companies from a subcategory of the financial sector to a new real estate sector. REITs represent approximately 3-4% of the market-capitalization of broad U.S. stock funds, which is a valid starting point for a REIT allocation in a diversified portfolio.33 REITs also offer exposure to some segments of the commercial real estate market (data centers and cell tower for instance) that aren’t as easy to access through traditional private real estate investment.

![]() For many, the question then becomes whether to overweight equity REITs beyond that index allocation given their strong historical performance. According to Nareit (which suggests pension funds target 15-20% allocations to real estate), the average pension fund has a 7% real estate allocation, but in November 2019, California State Teachers' Retirement System (one of the largest U.S. plans) increased its long-term real estate allocation target from 13 percent to 15 percent and was seeking to invest in undervalued public REITs.34 Burton Malkiel also recently suggested long-term investors target higher real estate allocations and younger people saving for retirement target 15-25% allocated to real estate.35

For many, the question then becomes whether to overweight equity REITs beyond that index allocation given their strong historical performance. According to Nareit (which suggests pension funds target 15-20% allocations to real estate), the average pension fund has a 7% real estate allocation, but in November 2019, California State Teachers' Retirement System (one of the largest U.S. plans) increased its long-term real estate allocation target from 13 percent to 15 percent and was seeking to invest in undervalued public REITs.34 Burton Malkiel also recently suggested long-term investors target higher real estate allocations and younger people saving for retirement target 15-25% allocated to real estate.35

![]() I am offering the online version of The Peaceful Investor using "The Honor System." If you don't plan to purchase a version of the book, yet you think it was worth your time and you learned a significant amount, you can tip or compensate me in a number of ways. This will probably not be tax deductible for you, but I will report and pay taxes on any payments.

I am offering the online version of The Peaceful Investor using "The Honor System." If you don't plan to purchase a version of the book, yet you think it was worth your time and you learned a significant amount, you can tip or compensate me in a number of ways. This will probably not be tax deductible for you, but I will report and pay taxes on any payments.