Buy The Peaceful Investor at Amazon

Table of Contents and Launch Site

I am offering the online chapters of the book using "The Honor System." Tip options at the bottom of the page.

Fidelity has a rule of thumb for how much you should save relative to your income to be able to retire at age 67. How many times your annual income should you have saved by age 50?

- 1 time your salary

- 3 times your salary

- 6 times your salary

- 10 times your salary

How do we determine whether an investor is lucky or has skill? It is a critical question that is asked far too infrequently in the investment business, and not enough people attempt to answer it. Unfortunately, it's also not a question that is easily answered in most cases. Statistical analysis of the probability of success due to skill is always subject to many assumptions, some of which tend to vary over time. Additionally, the average tenure of portfolio managers is typically relatively short (usually much less than a decade), which is usually less than the time required to estimate with much certainty whether skill or luck is responsible for any outperformance or underperformance.

I believe there are some rare very skilled investors, but I have some unique experiences that allow me to make that statement and it's very complicated to attempt to identify them and invest with them in advance. Not only have I worked directly with some talented managers that I believe have skill, I've had the opportunity to analyze their trades (for them) over extended periods, so I've personally seen cases that lead me to believe there are clear examples of skill in investing and security selection. However, I believe the skillful managers are a very small minority of the number of managers that think they have skill (many of which manage tremendous amounts of money).

There are many "buts" in trying to profit from skilled managers. First, it's very difficult to identify them in advance, especially without proprietary information. Second, once they become successful they tend to attract significant assets, thus making it harder to take advantage of their skill. Some successful managers appropriately close their funds to additional investments when they think the assets have gotten too large to take advantage of the available opportunities. Third, it's not unusual for teams to split up, or for staff members with knowledge of the skill to break off, which can ultimately lead to more money chasing the same strategies. Fourth, unsuccessful active management efforts tend to get terminated, while successful efforts tend to survive, creating a survivorship bias issue that often complicates the analysis.

Despite all the complications, there have been some very serious and professional studies addressing the question of whether skill can be differentiated from luck in the investment business. The bottom line is that it is very complicated and difficult to identify skilled managers.

Eugene Fama and Ken French published an extensive analysis of theoretical and actual results for active managers in the October 2010 edition of the Journal of Finance titled "Luck versus Skill in the Cross Section of Mutual Fund Returns." They found some true winners among fund managers, but looking at after costs returns to investors, the vast majority of funds could not add value.1

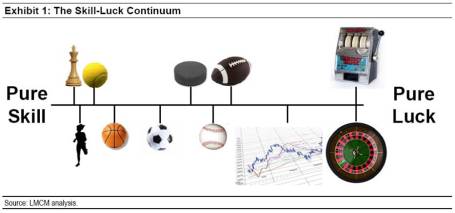

Michael Mauboussin is the author of The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing, which was published in 2012. His clever graphic "The Skill-Luck Continuum" (the graphic above is a version from this page) ranks games and activities on a scale from pure luck to pure skill. Chess, running, and tennis are at the far end of the pure skill scale, while roulette and slot machines are at the far end for pure luck. In a separate paper Mauboussin concluded "The success equation in investing includes both skill and luck, with the reality being that a lot of investing success falls more toward the luck side of the continuum.”2

John Rogers summarized in Forbes "investing is not like playing chess, where a highly skilled player will beat a novice almost every time, nor is it like playing a slot machine, where there is no skill involved. Rather, it is like poker, where a good player can lose if he gets dealt a bad hand."3

Other researchers have also demonstrated that it is extremely difficult to identify managers with enough skill to outperform after costs including Laurent Barras, O. Scaillet, and Russ Wermers who published “False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimating Alphas” in The Journal of Finance in February of 2010.4

According to Jeremy Siegel (in Stocks for the Long Run), in order to be able to say with 95% confidence that a fund manager’s performance is due to skill rather than luck, he’d need to outperform the market by an average of 4% per year for roughly 15 years. (If the fund was only outperforming by 3% annually, it would take more than 20 years.)

According to Barr Rosenberg, it would take 70 years of observations to show conclusively that even 2% of incremental annual return resulted from superior investment management skill rather than chance.5

Let’s start with the Investment Industry component. It is so obvious in this business that it’s a zero sum game. We collectively add nothing but costs. We produce no widgets; we merely shuffle the existing value of all stocks and all bonds in a cosmic poker game. At the end of each year, the investment community is behind the markets in total by about 1% costs and individuals by 2%. And the costs have steadily grown. As our industry’s assets grew tenfold from 1989 to 2007, despite huge economics of scale, the fees per dollar also grew. There was no fee competition, contrary to theory. Why? Clients can’t easily distinguish talent from luck or risk taking.

Jeremy Grantham in “2000-2009 Review” from GMO, LLC

Do Past Winners Repeat?

Are mutual fund managers and funds that have performed well in the past likely to have strong performance that persists in the future? The question of whether we can predict future performance from past performance is related to the skill versus luck debate. Mutual fund tracking services, periodicals, and web sites publish top performing funds on a continuing basis. However, if past performance does not predict future performance, this information is of little use in selecting mutual funds and managers going forward. While there have been some studies showing that strong performers continue to outperform over certain periods, many other studies have demonstrated that investors should not expect recent strong performers to outperform in the future.

![]() Ronald Kahn and Andrew Rudd concluded in "Does Historical Performance Predict Future Performance?" in the Financial Analysts Journal (November/December 1995) that there is some evidence of persistence in fixed income funds, but they came to the conclusion that both equity and fixed income investors may be better served by investing in index funds as opposed to funds that have performed well in the past.

Ronald Kahn and Andrew Rudd concluded in "Does Historical Performance Predict Future Performance?" in the Financial Analysts Journal (November/December 1995) that there is some evidence of persistence in fixed income funds, but they came to the conclusion that both equity and fixed income investors may be better served by investing in index funds as opposed to funds that have performed well in the past.

![]() Another study by Burton Malkiel in the June 1995 edition of Journal of Finance titled “Returns from Investing in Equity Mutual Funds 1971 to 1991” also addressed the issue.6 Numerous studies had demonstrated persistence in performance in the 1970s and Malkiel confirmed these findings, but found no consistency in the 1980s. Malkiel specifically examined the issue of survivorship bias - the fact that poor performing mutual funds tend to disappear (commonly by merging into more successful funds) "thereby burying the fund's bad record with it." Approximately 3% of mutual funds disappeared every year (for that period). The result is that many long term performance records do not include the records of poor performing funds that no longer exist. By examining all mutual funds that existed at the time, Malkiel determined "that survivorship bias is considerable more important than previous studies have suggested." Malkiel admitted that the analysis provided some support for buying funds with excellent records since they outperformed during certain periods and do no worse than the average fund, however he presented three caveats. First, the results were not robust, second, the returns were not actually achievable because of load charges and third, survivorship bias has to be accounted for. He concluded "It does not appear that one can fashion a dependable strategy of generating excess returns based on a belief that long-run mutual fund returns are persistent … Most investors would be considerably better off by purchasing a low expense index fund, than by trying to select an active fund manager who appears to possess a ‘hot hand.’"

Another study by Burton Malkiel in the June 1995 edition of Journal of Finance titled “Returns from Investing in Equity Mutual Funds 1971 to 1991” also addressed the issue.6 Numerous studies had demonstrated persistence in performance in the 1970s and Malkiel confirmed these findings, but found no consistency in the 1980s. Malkiel specifically examined the issue of survivorship bias - the fact that poor performing mutual funds tend to disappear (commonly by merging into more successful funds) "thereby burying the fund's bad record with it." Approximately 3% of mutual funds disappeared every year (for that period). The result is that many long term performance records do not include the records of poor performing funds that no longer exist. By examining all mutual funds that existed at the time, Malkiel determined "that survivorship bias is considerable more important than previous studies have suggested." Malkiel admitted that the analysis provided some support for buying funds with excellent records since they outperformed during certain periods and do no worse than the average fund, however he presented three caveats. First, the results were not robust, second, the returns were not actually achievable because of load charges and third, survivorship bias has to be accounted for. He concluded "It does not appear that one can fashion a dependable strategy of generating excess returns based on a belief that long-run mutual fund returns are persistent … Most investors would be considerably better off by purchasing a low expense index fund, than by trying to select an active fund manager who appears to possess a ‘hot hand.’"

![]() Malkiel also discussed Forbes Magazine "honor roll" which ranked mutual funds for performance in both up and down markets. Over the 16-year period from 1975 to 1991, the "honor role" underperformed the S&P 500. Further, the results ignored load charges which would have reduced performance. Malkiel also analyzed mutual fund fees to determine whether higher fees resulted in better performance. The study found "essentially no relationship between gross investment returns and expenses." Malkiel concluded that "The data do not give one much confidence that investors get their money's worth from investment advisory expenditures."

Malkiel also discussed Forbes Magazine "honor roll" which ranked mutual funds for performance in both up and down markets. Over the 16-year period from 1975 to 1991, the "honor role" underperformed the S&P 500. Further, the results ignored load charges which would have reduced performance. Malkiel also analyzed mutual fund fees to determine whether higher fees resulted in better performance. The study found "essentially no relationship between gross investment returns and expenses." Malkiel concluded that "The data do not give one much confidence that investors get their money's worth from investment advisory expenditures."

![]() Mark Carhart did extensive research on survivorship bias and authored “On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance” in the March 1997 issue of the Journal of Finance.7 Carhart concluded that "The results do not support the existence of skilled or informed mutual fund portfolio managers."

Mark Carhart did extensive research on survivorship bias and authored “On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance” in the March 1997 issue of the Journal of Finance.7 Carhart concluded that "The results do not support the existence of skilled or informed mutual fund portfolio managers."

![]() Mark Hulbert writing at the Wall Street Journal at the start of 2019 pointed out that you would expect 25% of the top quarter managers in one year to rank in the top quarter the following year, but according to Aye Soe of S&P Dow Jones Indices, the actual percentage is rarely higher than 20%.8

Mark Hulbert writing at the Wall Street Journal at the start of 2019 pointed out that you would expect 25% of the top quarter managers in one year to rank in the top quarter the following year, but according to Aye Soe of S&P Dow Jones Indices, the actual percentage is rarely higher than 20%.8

![]() Regarding hedge funds, Stephen Brown, William Goetzmann, and Roger Ibbotson found "no evidence of performance persistence in raw returns or risk-adjusted returns, even when we break funds down according to their returns-based style classification." They concluded that "the hedge fund arena provides no evidence that past performance forecasts future performance."9

Regarding hedge funds, Stephen Brown, William Goetzmann, and Roger Ibbotson found "no evidence of performance persistence in raw returns or risk-adjusted returns, even when we break funds down according to their returns-based style classification." They concluded that "the hedge fund arena provides no evidence that past performance forecasts future performance."9

![]() Xiaoqing Xu, Jiong Liu, and Anthony Loviscek studied hedge fund data from January of 1994 to March of 2009 and they identified "a hidden survivorship bias attributed to the lack of reporting during the final months of the eventual demise of a fund. We also find unprecedented attrition rates, along with record declines in assets under management and fund closures during the crisis.”10

Xiaoqing Xu, Jiong Liu, and Anthony Loviscek studied hedge fund data from January of 1994 to March of 2009 and they identified "a hidden survivorship bias attributed to the lack of reporting during the final months of the eventual demise of a fund. We also find unprecedented attrition rates, along with record declines in assets under management and fund closures during the crisis.”10

![]() Researchers have demonstrated in recent decades that survivorship bias can play a significant role in biasing past returns of individual securities, mutual funds, and even equities of specific countries. For example, William Goetzmann and Philippe Jorion pointed out that the high historical returns from American stocks may represent an exception rather than the rule when evaluating equity premiums in a worldwide context. Their paper “Global Stock Markets in the Twentieth Century” in the June 1999 issue of the Journal of Finance was a Smith Breeden Prize winner (awarded annually to the top papers in the Journal).11

Researchers have demonstrated in recent decades that survivorship bias can play a significant role in biasing past returns of individual securities, mutual funds, and even equities of specific countries. For example, William Goetzmann and Philippe Jorion pointed out that the high historical returns from American stocks may represent an exception rather than the rule when evaluating equity premiums in a worldwide context. Their paper “Global Stock Markets in the Twentieth Century” in the June 1999 issue of the Journal of Finance was a Smith Breeden Prize winner (awarded annually to the top papers in the Journal).11

![]() Unlike mutual funds and hedge funds, there is significant evidence or performance persistence in venture capital and leveraged buyout (LBO) funds.12 Yet, Some LBO fund sponsors also have had a tendency to leave out all the details when reporting their performance. In "The facts, but not all the facts" (Forbes 3/9/1998) a telling quote from the article was "There is no legal requirement that the dealmaker must present a full picture of his or her career.”

Unlike mutual funds and hedge funds, there is significant evidence or performance persistence in venture capital and leveraged buyout (LBO) funds.12 Yet, Some LBO fund sponsors also have had a tendency to leave out all the details when reporting their performance. In "The facts, but not all the facts" (Forbes 3/9/1998) a telling quote from the article was "There is no legal requirement that the dealmaker must present a full picture of his or her career.”

![]() A technique that some companies use in launching new products is to "incubate" funds. For example, a company wishing to launch a new series of mutual funds might provide ten managers with a small amount of seed money to start aggressive funds. Each manager is given two years to test their stock picking ability. At the end of the period several of the funds are likely to have outperformed. Those successful funds are then made available to the public and marketed aggressively while the losers are silently discontinued. This is what is known as "creation bias."

A technique that some companies use in launching new products is to "incubate" funds. For example, a company wishing to launch a new series of mutual funds might provide ten managers with a small amount of seed money to start aggressive funds. Each manager is given two years to test their stock picking ability. At the end of the period several of the funds are likely to have outperformed. Those successful funds are then made available to the public and marketed aggressively while the losers are silently discontinued. This is what is known as "creation bias."

![]() Once you have an appreciation for the effects of survivorship and creation bias it’s easy to see how companies can effectively guarantee long term records of outperformance. By starting with a large number of funds and discontinuing or merging the poor performers, a company is left with a stable of cherry-picked winners. Even if a surviving fund only matches the returns of the market going forward, its long term record will continue to be better than the market as a result of the initial outperformance.

Once you have an appreciation for the effects of survivorship and creation bias it’s easy to see how companies can effectively guarantee long term records of outperformance. By starting with a large number of funds and discontinuing or merging the poor performers, a company is left with a stable of cherry-picked winners. Even if a surviving fund only matches the returns of the market going forward, its long term record will continue to be better than the market as a result of the initial outperformance.

![]() Another issue that investors should keep in mind is the tendency for strong performing funds to grow rapidly which has many implications. Many funds that outperform experience large inflows and are subsequently unable to repeat the performance with substantially higher assets under management. It’s also common for funds that outperform over short periods of time to turn around in the following period and underperform. The underperformance frequently occurs with more assets under management. The result is often a fund with an average track record, but overall investors in the fund underperformed.13

Another issue that investors should keep in mind is the tendency for strong performing funds to grow rapidly which has many implications. Many funds that outperform experience large inflows and are subsequently unable to repeat the performance with substantially higher assets under management. It’s also common for funds that outperform over short periods of time to turn around in the following period and underperform. The underperformance frequently occurs with more assets under management. The result is often a fund with an average track record, but overall investors in the fund underperformed.13

![]() The following is a simplistic and fictional example, but similar scenarios occur regularly in the investment business. A little-known stock fund with $10 million in assets experiences a period of significant outperformance rising 50% over the course of a year. As a result, the fund (now $15 million in assets) receives a significant amount of publicity and investors flock to the fund. The fund quickly grows to $150 million. The fund then proceeds to lose 10% over the following year.

The following is a simplistic and fictional example, but similar scenarios occur regularly in the investment business. A little-known stock fund with $10 million in assets experiences a period of significant outperformance rising 50% over the course of a year. As a result, the fund (now $15 million in assets) receives a significant amount of publicity and investors flock to the fund. The fund quickly grows to $150 million. The fund then proceeds to lose 10% over the following year.

![]() What is the funds return over the two years? A positive 35% (a little over 16% annually) since the original investors put in $10 million and would then have $13.5 million. Yet investors in aggregate have lost more money in the fund than they've made. Gains in the first year were $5 million while losses in the second year where $15 million. The fund has a 2 year track record of 16% annualized returns but investors in the fund are down $10 million. The example demonstrates the difference between time-weighted and dollar-weighted returns, which I’ll discuss further in Chapter 11.

What is the funds return over the two years? A positive 35% (a little over 16% annually) since the original investors put in $10 million and would then have $13.5 million. Yet investors in aggregate have lost more money in the fund than they've made. Gains in the first year were $5 million while losses in the second year where $15 million. The fund has a 2 year track record of 16% annualized returns but investors in the fund are down $10 million. The example demonstrates the difference between time-weighted and dollar-weighted returns, which I’ll discuss further in Chapter 11.

![]() These issues demonstrate the importance of being skeptical of performance claims, particularly when the claims are coming from the company itself. Also keep in mind that there are numerous ranking systems which increase the likelihood that each fund will be highly ranked by someone over some period of time. Past decisions by the NASD and SEC regarding track records also complicate some of these issues. In many cases track records will be movable by managers which could create more confusion.

These issues demonstrate the importance of being skeptical of performance claims, particularly when the claims are coming from the company itself. Also keep in mind that there are numerous ranking systems which increase the likelihood that each fund will be highly ranked by someone over some period of time. Past decisions by the NASD and SEC regarding track records also complicate some of these issues. In many cases track records will be movable by managers which could create more confusion.

![]() Firms that comply with the Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS®) from the CFA Institute are generally not subject to the cherry-picking problem. The standards require all accounts under management to be included in at least one composite that is included in their performance reports. Therefore firms that comply can't hide poor performance from their record.

Firms that comply with the Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS®) from the CFA Institute are generally not subject to the cherry-picking problem. The standards require all accounts under management to be included in at least one composite that is included in their performance reports. Therefore firms that comply can't hide poor performance from their record.

![]() Hedge Funds provide another unique example of the importance of evaluating survivorship bias. A well written summary of the major bias issues with Hedge Fund performance reporting can be found in “Hidden Survivorship in Hedge Fund Returns” by Rajesh Aggarwal and Philippe Jorion in the March/April 2010 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal.14 They discovered a major problem that could have inflated a prior database returns by 5%.

Hedge Funds provide another unique example of the importance of evaluating survivorship bias. A well written summary of the major bias issues with Hedge Fund performance reporting can be found in “Hidden Survivorship in Hedge Fund Returns” by Rajesh Aggarwal and Philippe Jorion in the March/April 2010 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal.14 They discovered a major problem that could have inflated a prior database returns by 5%.

![]() Hedge fund managers typically report their funds’ performance to databases only voluntarily. Therefore the common indices of hedge fund returns usually have two types of biases. First, "backfill bias, which occurs when a fund’s performance is not made public during an incubation period but is added to a database later, likely following good performance." Second, "survivorship bias, which occurs when funds that no longer report are dropped from the database of 'live' funds." Burton Malkiel and Atanu Saha found each of those biases averaged over 4%. Malkiel and Saha's paper was titled “Hedge Funds: Risk and Return” and appeared in the Nov/Dec 2005 edition of the Financial Analysts Journal.15 They concluded that "hedge funds are riskier and provide lower returns than is commonly supposed." Further, "Investors in hedge funds take on a substantial risk of selecting a dismally performing fund or, worse, a failing one."

Hedge fund managers typically report their funds’ performance to databases only voluntarily. Therefore the common indices of hedge fund returns usually have two types of biases. First, "backfill bias, which occurs when a fund’s performance is not made public during an incubation period but is added to a database later, likely following good performance." Second, "survivorship bias, which occurs when funds that no longer report are dropped from the database of 'live' funds." Burton Malkiel and Atanu Saha found each of those biases averaged over 4%. Malkiel and Saha's paper was titled “Hedge Funds: Risk and Return” and appeared in the Nov/Dec 2005 edition of the Financial Analysts Journal.15 They concluded that "hedge funds are riskier and provide lower returns than is commonly supposed." Further, "Investors in hedge funds take on a substantial risk of selecting a dismally performing fund or, worse, a failing one."

![]() In a separate paper, Alex Grecu, Burton Malkiel and Atanu Saha summarized that "most funds stop reporting not because they are ‘too successful,’ but rather because they fail."16 Similarly, John Griffin and Jin Xu questioned the skill and performance persistence of Hedge Funds and concluded with the following. "The sector timing ability and average style choices of hedge funds are no better than that of mutual funds. Additionally, we fail to find differential ability between hedge funds. Overall, our study raises serious questions about the proficiency of hedge fund managers."17

In a separate paper, Alex Grecu, Burton Malkiel and Atanu Saha summarized that "most funds stop reporting not because they are ‘too successful,’ but rather because they fail."16 Similarly, John Griffin and Jin Xu questioned the skill and performance persistence of Hedge Funds and concluded with the following. "The sector timing ability and average style choices of hedge funds are no better than that of mutual funds. Additionally, we fail to find differential ability between hedge funds. Overall, our study raises serious questions about the proficiency of hedge fund managers."17

![]() Craig Lazzara at S&P wrote in October of 2017 that over the prior ten years, funds that were in the top quartile for the first five years were more likely to move to the bottom quartile than to remain at the top." He summarized "If low expense ratios are predictive of returns, it follows that ‘you get what you pay for’ is wrong, at least in a general sense. If you got what you paid for, high-expense ratio funds would outperform low-expense ratio funds. If you don’t, that’s a powerful argument in favor of the kind of mean reversion we persistently see in our Persistence Scorecards."18

Craig Lazzara at S&P wrote in October of 2017 that over the prior ten years, funds that were in the top quartile for the first five years were more likely to move to the bottom quartile than to remain at the top." He summarized "If low expense ratios are predictive of returns, it follows that ‘you get what you pay for’ is wrong, at least in a general sense. If you got what you paid for, high-expense ratio funds would outperform low-expense ratio funds. If you don’t, that’s a powerful argument in favor of the kind of mean reversion we persistently see in our Persistence Scorecards."18

"If you pay the executives at Sarah Lee more, it doesn't make the cheesecake less good. But with mutual funds, it comes directly out of the batter."

Don Phillips (Morningstar President) in U.S. News & World Report, July 8, 1996

![]() Regarding the question at the start of the chapter, according to Fidelity, to retire at 67 you should plan to save 10 times your salary. By the age of 50 you should save 6 times your salary to retire at 67. See https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirement/how-much-do-i-need-to-retire.

Regarding the question at the start of the chapter, according to Fidelity, to retire at 67 you should plan to save 10 times your salary. By the age of 50 you should save 6 times your salary to retire at 67. See https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirement/how-much-do-i-need-to-retire.

![]() I am offering the online chapters of The Peaceful Investor using "The Honor System." If you don't plan to purchase a version of the book, yet you think it was worth your time and you learned a significant amount, you can tip or compensate me in a number of ways. This will probably not be tax deductible for you, but I will report and pay taxes on any payments.

I am offering the online chapters of The Peaceful Investor using "The Honor System." If you don't plan to purchase a version of the book, yet you think it was worth your time and you learned a significant amount, you can tip or compensate me in a number of ways. This will probably not be tax deductible for you, but I will report and pay taxes on any payments.